The plan to electrify the Padalarang–Cicalengka railway line is once again under discussion, with Indonesian Minister of Transportation Dudy Purwagandhi recently revealing key details about this 42-kilometer project.

As quoted by Tempo, Dudy stated that electrified commuter trains on the Padalarang–Cicalengka route are targeted to be operational no later than 2027. The presence of these electric trains is expected to cut travel time between the two stations from two hours to just one[1].

If this plan can be realized, it will finally bring an end to the long wait for railway electrification in the Bandung area. This wait has lasted for more than a century. To understand why it took so long, we need to look back at how the idea of electrification first emerged in the Dutch East Indies.

According to Simeon[2], electric trains were chosen for their clear advantages over conventional trains pulled by steam locomotives. These benefits drew the attention of the Dutch East Indies government, especially as similar technology was already being adopted in Europe and North America. In the Netherlands, electrified lines began operating in 1908, connecting Rotterdam and Gravenhage[3].

Research into the feasibility of implementing this technology in the Dutch East Indies had been underway since 1911. However, plans to develop an electric railway network were hampered by the outbreak of the First World War. The conflict caused the price of coal—the primary fuel for electricity generation at the time—to skyrocket.

Things began to change after P. A. Roelofsen, Head of the Water Power and Electricity Department at the Gouvernements Bedrijven, proposed using hydropower as an energy source for electric trains in the Dutch East Indies. In 1915, he began researching the possibility of electrifying several railway lines, including those in the Bandung highlands[4].

In developing the electric railway network in the Dutch East Indies, the Water Power and Electricity Service was responsible for constructing the central power plants (centrale). It also handled the cable network leading to the substations. The substations themselves were built and managed by the Staatsspoorwegen (SS). In addition to constructing the substations, the SS was also responsible for constructing and maintaining cables along the railway line[5].

The first electrification project in the Dutch East Indies was carried out in Batavia and its surrounding areas. The electricity for this line came from the Cicatih River in Sukabumi and the Cianten River in Bogor, supplied through the Oebroeg and Kratjak centrales[6]. The electric railway network officially began operating on April 6, 1925[7].

Meanwhile, in Bandung, the discourse initiated by Roelofsen gradually faded. By the late 1910s, the topic of electrification had all but disappeared. It no longer appeared even in discussions about improving the city’s railway system. The reform efforts at that time involved improving transportation facilities to support the planned relocation of the capital of the Dutch East Indies from Batavia to Bandung. This grand plan prompted the city government to undertake various improvements for the convenience of the public and the smooth functioning of the central government.

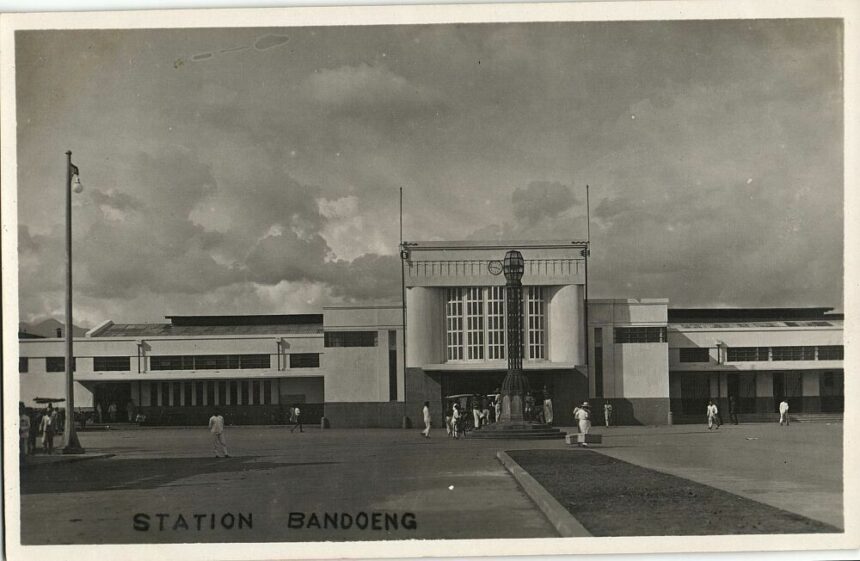

In these improvements, the city government collaborated with the Staatsspoorwegen (State Railways) to streamline the movement of passengers and goods. The aim was to prevent road traffic from being disrupted by heavy rail activity. These measures were also expected to make train travel within the city more efficient, even as both passenger numbers and train frequency continued to rise. Notable outcomes of the 1920s improvements included the construction of the Padalarang–Kiaracondong double-track line, the Pasirkaliki Viaduct, and the Bandung Goederenstation (Bandung Gudang Station).

Although Bandung’s electricity infrastructure was already quite advanced at the time, the discourse on electrification had largely disappeared. The author argues that this disappearance was related to a lack of funding.

In terms of infrastructure, Bandung planned to have several hydroelectric power plants (PLTA) around the city, such as Bengkok, which utilizes the flow of the Cikapundung River, and Plengan and Lamajan, which utilize the flow of the Cisangkuy River. These power plants supported the energy supply for residents and industry, and even supported the operation of the Malabar Radio Station[8].

However, the colonial government likely lacked the funds to develop electric train infrastructure in Bandung. In the end, the government completed the double track between Padalarang Station and Kiaracondong Station only around 1924[9].

Since then, the discourse on electrification in Bandung has completely disappeared. The plan that once sat on the desks of colonial officials was never realized. Only a century later did the Indonesian government revive the very same idea.

References:

[1] Elektrifikasi Kereta Komuter Padalarang-Cicalengka Ditargetkan Rampung 2027. Link: https://www.tempo.co/ekonomi/elektrifikasi-kereta-komuter-padalarang-cicalengka-ditargetkan-rampung-2027-2078349

[2] Simeon, R. Oerip. 1953. Sedjarah Kereta Api Negara (SS/DKA) di Indonesia. Bandung: Pengurus besar Persatuan Buruh Kereta Api. Hal. 31.

[3] Simeon, R. Oerip. 1953. Sedjarah Kereta Api Negara (SS/DKA) di Indonesia. Bandung: Pengurus besar Persatuan Buruh Kereta Api. Hal. 31.

[4] Reitsma, S. A. 1915. Indische Spoorwegpolitiek Deel VIII: De spoorwegtoestanden te Batavia. Weltevreden: Landsdrukkerij. Halaman 211.

[5] Simeon, R. Oerip. 1953. Sedjarah Kereta Api Negara (SS/DKA) di Indonesia. Bandung: Pengurus besar Persatuan Buruh Kereta Api. Hal. 31.

[6] Reitsma, S.A. 1925. Staatsspoor en Tramwegen in Nederlandsch Indie 1875-1925. Weltevreden. Hal. 162.

[7] Reitsma, S. A. 1915. Indische Spoorwegpolitiek Deel VIII: De spoorwegtoestanden te Batavia. Weltevreden: Landsdrukkerij. Halaman 235.

[8] Stroomberg, J. 2018. Hindia belanda 1930. Terjemahan. Yogyakarta: IRCISoD. Halaman 291.

[9] Reitsma, S. A. 1915. Indische Spoorwegpolitiek Deel VIII: De spoorwegtoestanden te Batavia. Weltevreden: Landsdrukkerij. Halaman 213.

Leave a Reply